Performance

Get a measurable indicator of application performance by considering Web Vitals.

Web Vitals are a set of metrics and factors that Google has assembled as indicators of a good user experience when using web applications.

Although there are different types of performance and each has its own underlying drivers, overall performance can be measured holistically using these indicators.

As a simple example, there are several techniques to cut down on image load time. You could use smaller images, higher compression, lower quality, geographic Content Delivery Network (CDN) edge caching, etc. Regardless of solution, image load time is the indicator being measured.

Some examples of the set of Web Vitals include:

- Time to First Byte (TTFB)

- First Contentful Paint (FCP)

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP)

- Total Blocking Time (TBT)

- Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS)

Those are great, but not all of them are measurable in the field, and not all of them directly reflect the end user experience.

Core Web Vitals

In order to pare the list of Web Vitals metrics down into those that are both measurable in the field and directly relevant to the end user experience, Google has designated a subset of these as Core Web Vitals.

These core indicators are intended to act as a relatively stable and standard set for developers to use to measure their end user experience. In order to stay relevant, but not disruptive, Google reevaluates the set of Core Web Vitals annually.

The current set for 2020 focuses on three aspects of the user experience—loading, interactivity, and visual stability—and includes the following metrics (and their respective thresholds):

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP): measures loading performance. To provide a good user experience, LCP should occur within 2.5 seconds of when the page first starts loading.

- First Input Delay (FID): measures interactivity. To provide a good user experience, pages should have a FID of 100 milliseconds or less.

- Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS): measures visual stability. To provide a good user experience, pages should maintain a CLS of 0.1 or less.

For each of the above metrics, to ensure you're hitting the recommended target for most of your users, Google recommends that a good threshold to measure is the 75th percentile of page loads, segmented across mobile and desktop devices.

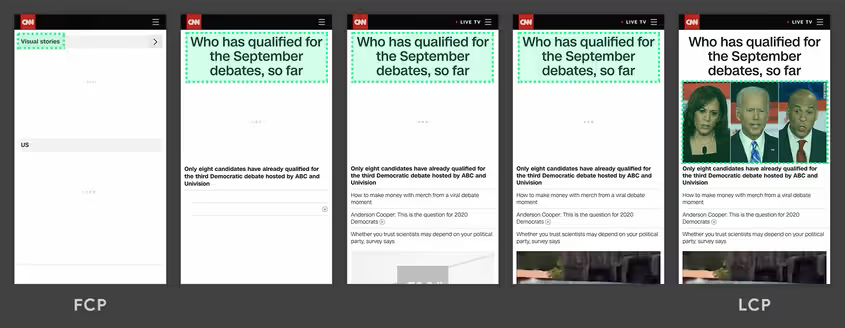

Largest Contentful Paint

The Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) metric reports the render time of the largest image or text block visible within the viewport, relative to when the page first started loading. To provide a good user experience, LCP should occur within 2.5 seconds of when the page first starts loading.

Historically, it's been a challenge for web developers to measure how quickly the main content of a web page loads and is visible to users. Measuring how long it takes to load the code doesn't necessarily translate to when users see content on their screen. By focusing on the user experience, and supported by research done at World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Google, a good measure is to look at when the largest element in the viewport was rendered.

As an example, below the first content paint occurs when the menu is rendered, but the largest content paint occurs when the headline image renders:

What is considered in LCP?

Not all page elements are meaningful when considering candidates for largest contentful paint. Only the following types of elements are considered:

<img>elements<image>elements inside an<svg>element<video>elements (the poster image is used)- An element with a background image loaded via the

url()function (as opposed to a CSS gradient) - Block-level elements containing text nodes or other inline-level text elements children.

For full details on LCP, refer to the Largest Contentful Paint API or the Google web.dev article about LCP.

How to improve LCP

LCP is primarily affected by four factors:

- Slow server response times

- Render-blocking JavaScript and CSS

- Resource load times

- Client-side rendering

Simple steps to improve LCP include optimization of static content (CSS, Images, Fonts, and JavaScipt), optimizing the Critical Rendering Path, and employing the PRPL pattern.

For more extensive resources for optimizing LCP, refer to the web.dev article about Optimizing LCP.

First Input Delay

First Input Delay (FID) measures the time from when a user first interacts with a page (i.e. when they click a link, tap on a button, or use a custom, JavaScript-powered control) to the time when the browser is actually able to begin processing event handlers in response to that interaction. To provide a good user experience, sites should strive to have a First Input Delay of 100 milliseconds or less.

It's one thing to have a site that renders quickly, but if the user can't interact with it because the browser is still busy doing other things, that's not great. For example, if your application executes a large chunk of JavaScript on load, event listeners and element actions may fail to run because the main thread is busy doing other things.

Consider the following example. The graphic shows a page that's making a couple of network requests for resources (most likely CSS and JS files), and — after those resources are finished downloading — they're processed on the main thread. This results in periods where the main thread is momentarily busy, which is indicated by the main thread task blocks.

Observe what would happen if a user tried to interact with a page near the beginning of the longest loading task:

Because the input occurs while the browser is in the middle of running a task, it has to wait until the task completes before it can respond to the input. The time it must wait is the FID value for this user on this page.

For full details on First Input Delay, refer to the Google web.dev article about FID.

How to improve FID

FID is primarily caused by heavy JavaScript execution on loading. Optimizing how JavaScript parses, compiles, and executes on your web page will directly reduce FID. Steps to improve this include:

- Break up long tasks

- Optimize your page for interaction readiness

- Use a web worker

- Reduce JavaScript execution time

For a more extensive deep-dive on optimizing FID, refer to the web.dev article about Optimizing FID.

Cumulative Layout Shift

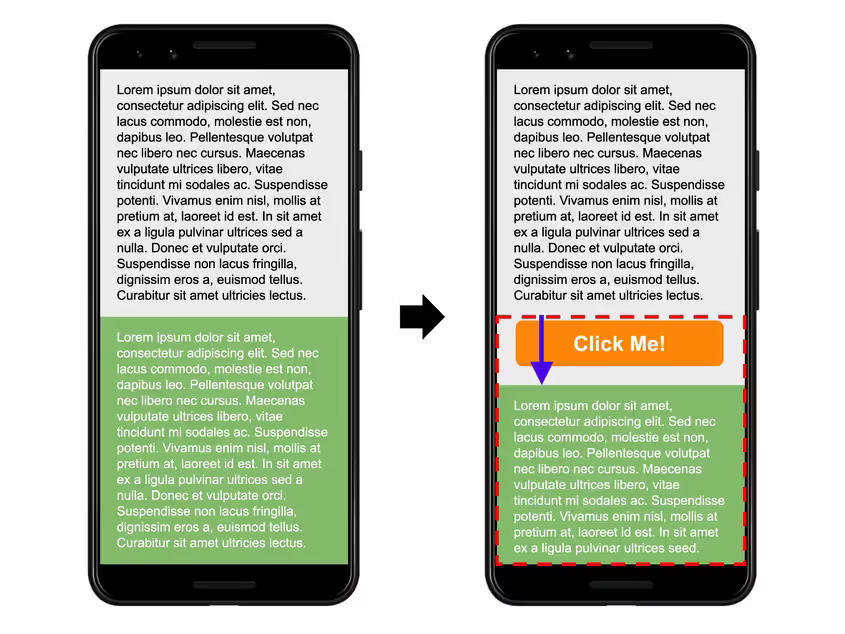

Layout Shift is what you experience when you're trying to click on something and, all of a sudden, an advertisement loads and the whole page shifts down to accommodate. It can simply be annoying, or it can be damaging - errant clicks taking you to places you don't want to go, submitting things you don't want to submit, and so on.

Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS) is a measure of the largest burst of layout shift scores for every unexpected layout shift that occurs during the entire lifespan of a page. To provide a good user experience, sites should strive to have a CLS score of 0.1 or less.

A layout shift occurs any time a visible element changes its position from one rendered frame to the next. (See below for details on how individual layout shift scores are calculated.)

A burst of layout shifts, known as a session window, is when one or more individual layout shifts occur in rapid succession with less than 1-second in between each shift and a maximum of 5 seconds for the total window duration.

The largest burst is the session window with the maximum cumulative score of all layout shifts within that window.

For full details on Cumulative Layout Shift, refer to the Google web.dev article about CLS.

How to improve CLS

CLS is typically caused by asynchronous content being loaded and rendered after other elements have already been rendered. For most cases, you can avoid all unexpected layout shifts by sticking to a few guiding principles:

- Always include size attributes on your images and video elements, or otherwise reserve the required space with something like CSS aspect ratio boxes. This approach ensures that the browser can allocate the correct amount of space in the document while the image is loading. Note that you can also use the unsized-media feature policy to force this behavior in browsers that support feature policies.

- Never insert content above existing content, except in response to a user interaction. This ensures any layout shifts that occur are expected.

- Prefer transform animations to animations of properties that trigger layout changes. Animate transitions in a way that provides context and continuity from state to state.

For a deep dive on how to improve CLS, refer to the Google web.dev article about Optimizing CLS.